A Comprehensive Analysis of Historical and Genetic Evidence

The question of Indo-European arrival in South Asia represents one of the most contentious and significant debates in the study of ancient populations. Recent advances in ancient DNA technology have fundamentally transformed our understanding of this complex historical process, moving scholarly consensus away from earlier invasion models toward a more nuanced migration and integration framework.

Historical Development of Theoretical Frameworks

Colonial Origins and Early Interpretations

The theoretical foundation for Indo-European migration into South Asia emerged during the colonial period, beginning with Sir William Jones’s seminal 1786 observation of linguistic similarities between Sanskrit, Latin, and Greek. This recognition of the Indo-European language family laid the groundwork for subsequent theories about population movements.

Key Historical Development: Max Müller and other 19th-century scholars developed what became known as the “Aryan Invasion Theory,” which proposed that nomadic Indo-European tribes violently conquered the indigenous Dravidian populations of the Indus Valley around 1500 BCE.

Archaeological Challenges to Invasion Models

The discovery and excavation of Harappan sites beginning in the 1920s initially seemed to support the invasion theory. Mortimer Wheeler’s influential interpretation in the mid-20th century suggested that the unburied corpses found at Mohenjo-daro represented victims of Aryan conquest, pointing to apparent destruction layers as evidence of warfare.

Critical Finding: However, subsequent archaeological work throughout the latter half of the 20th century increasingly challenged this narrative. Systematic excavations revealed no clear evidence of mass violence, foreign weapons, or sudden cultural displacement at major Harappan sites.

Genetic Revolution: Ancient DNA Evidence

Breakthrough Studies and Methodological Advances

The application of ancient DNA technology to South Asian prehistory has revolutionized scholarly understanding of population movements and genetic continuity. The most significant breakthrough came with the 2019 publication of two landmark studies: a comprehensive analysis of 523 ancient individuals across Central and South Asia published in Science, and the first successful extraction of Harappan DNA from Rakhigarhi published in Cell.

Timeline of Key Genetic Discoveries

The Genetic Structure of Ancient South Asia

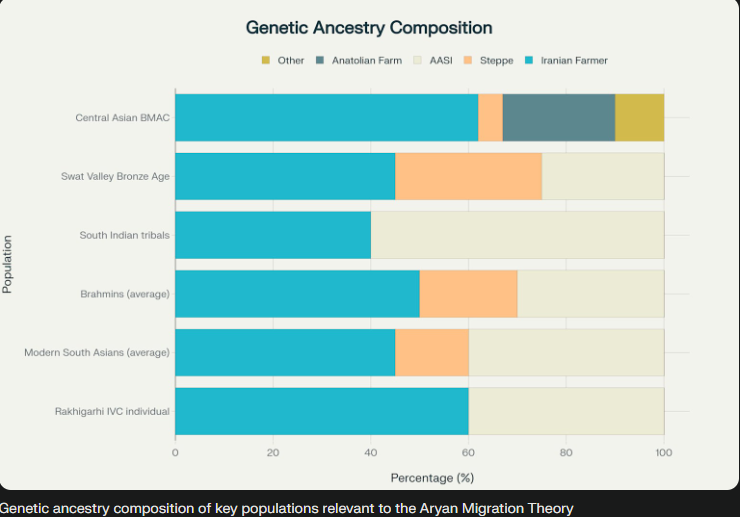

Ancient DNA research has revealed a complex three-source model for South Asian populations, fundamentally challenging earlier binary frameworks. The genetic landscape is characterized by three major ancestry components:

Iranian Farmer-Related Ancestry

Arriving around 7000 BCE, this component represents early agricultural populations that contributed significantly to Indus Valley Civilization genetics.

Ancient Ancestral South Indian (AASI)

The deepest indigenous component representing the original hunter-gatherer populations of South Asia.

Steppe Pastoralist Ancestry

Arriving much later (2000-1500 BCE), associated with Indo-European language spread and showing strong male bias in genetic contribution.

Indus Periphery Cline: A crucial genetic gradient identified through analysis of 11 outlier individuals from sites in cultural contact with the Indus Valley Civilization. This cline, characterized by varying proportions of Iranian farmer-related and AASI ancestry, likely represents the genetic signature of IVC populations and forms the largest ancestral component of modern South Asians.

Archaeological Context and Material Culture Evidence

The Indus Valley Civilization: Urban Sophistication and Peaceful Decline

The Indus Valley Civilization, flourishing from approximately 2600 to 1900 BCE, represents one of the world’s earliest urban civilizations, covering an area larger than Mesopotamia and Egypt combined. Major urban centers including Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, Dholavira, and Rakhigarhi demonstrate sophisticated urban planning, standardized weights and measures, and advanced drainage systems.

Archaeological Evidence: Archaeological evidence from these sites reveals no clear indicators of warfare or violent destruction. The absence of fortifications at most major centers, the lack of weapons in archaeological assemblages, and the planned, peaceful abandonment of urban areas all point to internal factors rather than external conquest as the primary drivers of civilizational decline.

Central Asian Steppe Cultures: Sintashta and Andronovo Complexes

The archaeological record of the Central Asian steppes provides crucial context for understanding the origins and material culture of groups associated with Indo-European expansion. The Sintashta culture (c. 2200-1800 BCE) represents a foundational development in this process, characterized by fortified settlements, advanced metallurgy, and the world’s earliest known spoked-wheel chariots.

The subsequent Andronovo cultural complex (c. 2000-1450 BCE) represents the geographical and temporal expansion of these traditions across the Eurasian steppes. Archaeological evidence suggests these cultures were associated with pastoral nomadism, bronze metallurgy, and horse domestication—innovations that would prove crucial for long-distance migration and cultural transmission.

Synthesis: Migration, Integration, and Cultural Transformation

The Modern Consensus: Migration Rather Than Invasion

Contemporary scholarship has reached a broad consensus supporting a migration and integration model rather than violent conquest. This framework, sometimes termed the “Modern Synthesis,” integrates linguistic, archaeological, and genetic evidence to propose a complex process of gradual migration, cultural exchange, and population mixing.

Genetic Evidence

Steppe ancestry arrived in South Asia between 2000-1500 BCE, showing strong male bias and integrating with existing populations rather than replacing them.

Archaeological Evidence

No evidence of mass violence or sudden cultural displacement. Gradual decline of IVC centers preceded main steppe migration period.

Linguistic Evidence

Sanskrit and Indo-Aryan languages developed through interaction of immigrant and indigenous populations, preserving non-Indo-European elements.

Language, Genetics, and Social Stratification

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence linking steppe ancestry to Indo-European languages comes from the genetic analysis of modern South Asian populations. Brahmin groups, traditionally associated with Sanskrit literature and Indo-European religious practices, show consistently higher levels of steppe ancestry compared to other populations. This pattern provides independent genetic support for the connection between steppe migration and language spread.

Impact on Indus Valley Populations

The relationship between Indo-European migration and Indus Valley decline remains complex and nuanced. Genetic evidence indicates that IVC populations were not replaced but rather contributed the largest single component to later South Asian ancestry. The decline of urban Harappan civilization appears to have preceded the main period of steppe migration, suggesting that internal factors—possibly including climate change, river system changes, or economic disruption—played primary roles in urban abandonment.

Post-Urban Period: However, the post-urban period saw significant population movements and cultural changes. Former IVC populations appear to have mixed with groups carrying higher levels of AASI ancestry to form the Ancestral South Indian (ASI) component, while simultaneous mixing with incoming steppe populations created the Ancestral North Indian (ANI) component. This dual process of population mixing established the basic genetic structure that characterizes South Asian populations today.

Conclusion

The investigation of historical and genetic evidence surrounding the Aryan Migration Theory and its impact on the Indus Valley Civilization reveals a complex process of gradual migration, cultural integration, and population mixing rather than violent conquest. Ancient DNA technology has revolutionized our understanding by providing direct genetic evidence that supports linguistic and archaeological findings while challenging simplistic invasion models.

Key Synthesis: The evidence demonstrates that Indo-European speakers arrived in South Asia during the second millennium BCE, bringing steppe ancestry that contributed to modern South Asian populations but did not replace existing groups. The Indus Valley Civilization appears to have declined due to internal factors, with its populations contributing the largest single component to later South Asian ancestry. The subsequent development of Indo-Aryan culture and Sanskrit literature represents a synthesis of immigrant and indigenous traditions rather than simple cultural replacement.

This modern synthesis framework, supported by converging lines of genetic, archaeological, and linguistic evidence, provides a nuanced understanding that moves beyond earlier binary models of invasion versus indigenous development. It acknowledges the complex, multicultural origins of South Asian civilization while recognizing the significant contributions of multiple population groups to the region’s rich cultural heritage.

Academic Research Foundation

This analysis is based on peer-reviewed research published in leading scientific journals including Science and Cell, with genetic findings replicated across multiple studies. The convergence of genetic, archaeological, and linguistic evidence supports the migration and integration model with high confidence based on current available evidence.

Imagined – Women from Rakhigarhi

Imagined: Aryan man from the Steppe

Genetic ancestry composition